It is hard to remain stoic having read Daniel Buren’s article on the function of the studio which was published in 1971. Less so to remain objective in a critique of his ideas. One could argue that, a lot of water has passed under the bridge, since he first expressed his views. On the other hand, it does seem strange that given what we know about the role and function of many artists’ studios, and how they have functioned and for a very long time, that his window of discourse seems to be so limited.

It might help to summarise in brief, the main points of his thesis as I understand it. He argues that the artist’s studio is firstly; a place where work originates; secondly, it is generally a private place, an ‘ivory tower’ even; and thirdly; it’s a stationary place, where portable objects are produced and then moved elsewhere. He develops his argument by stating that the studio is an archetype of which there are essentially two types – one based on the Parisian model circa the end of the 19th century and the other based on the American one located in reclaimed lofts originating from the 1950s onwards.

His assertions seem reductive, but I wonder whether he is indulging in rhetorical gymnastics in order to provoke debate about the studio vs. gallery split (apart from the comment on his own work). This is a generous assumption, as it would be easier to question the differences and to make more profound comments, if he appeared more reflective. Now, I am lurching into making reductive comments in response.

To take his first point, that the studio is where art originates. He seems to argue that because work is made in the studio, then it can be said that the work really only belongs in the studio. The work is, once moved from the studio space, “totally foreign to the world into which it is welcomed (museum, gallery or collection). Inevitably, this leads to a tension, he argues, or indeed falls into an ever-widening abyss “hurling the entire parade of art into historical oblivion”.

It does appear to be a naive understanding of the imperatives and intentionality under which the majority of artists produce work. For example, in my own work, most pieces are envisaged in my head, a combination of idea, influence, concept and theory, before ever they see the light of day in the studio or the workshop. And even before that, many will be committed to a sketchbook or scrap of paper. To follow his logic, therefore, there might well be another category: the sketchbook verses the studio perhaps, or the imagination vs. the scrap of paper even? It seems to me, that this argument is destined to forever chase its own tail and unlikely to provide meaningful insight into the creative process or the display of the outcome.

Another other implication of his argument is that it implies that an artist cannot envisage the final location for an artwork when it is being produced in the studio. Indeed, many artists are commissioned to produce work for specific places and take huge amounts of trouble over the piece and how it’ll work in its intended location like the installation piece for the Museum of Contemporary Art, by Robert Gober ‘untitled 1995-1997’. In my opinion, it would be quite wrong to suggest that the work is somehow diminished because it was fabricated/painted/printed/sculpted in one place (the studio or workshop) and hung or installed in another.

Robert Gober Untitled

The second suggestion Buren makes is that the studio is an essentially private place. This is partly true as it is a place of work and not a public viewing opportunity. However, many artists sell directly from their studio to the public, collectors or dealers and therefore, it is frequently a more public environment than perhaps Buren gives credit. (He does acknowledge this in the article but fails, in my opinion, to follow the logic of his own argument). He makes a subsidiary point in relation to the studio’s alleged privacy by suggesting that the studio is also an ‘ivory tower’. I find this point hard to understand in his overall thesis. Does he seriously believe a place of work for artists is something remote, exalted and removed from the real world? This seems seriously at odds with the fact that most artists live precarious existences on the edge of poverty inhabiting the cheaper parts of towns and cities often living cheek-by-jowl with the poor and are themselves often deeply sensitive and thoughtful individuals whose practice is intricately entwined with their histories and lives. To suggest that they inhabit remote and privileged places therefore is not born out by the evidence.

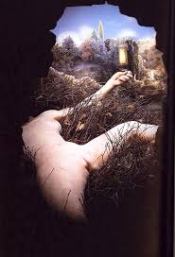

It may be true, and Buren hints at this, that some artworks end up in lofty places, but that is not to say that they were conceived in them! After all, if a dog is born in a stable does not make it a horse. Curiously, Buren goes on to say that a gallery is tantamount to being a cemetery for art works: “this is where they all arrive in the end, where they are lost”. He balances this, and to an extent his essay seeks to have it all ways, by stating that the graveyard of the gallery is as ‘nothing to the oblivion faced by those works that never make it out of the studio’. Again, I find this hard to reconcile with empirical evidence. This is not true for example of the work that Duchamp was working on secretly in his studio between 1946 and 1966 ‘Etant donnes’ or the black paintings of Goya’s house. The reputation of these works blossomed after their hidden studio genesis.

Marcel Duchamp Etant donnes

The third point Buren makes, is one about art being made in a stationary place and then moved to somewhere else. He talks of ‘the unspeakable compromise of the portable object’. But this to my mind suggests a truism which reflects little on the status or life cycle of an artwork over time.

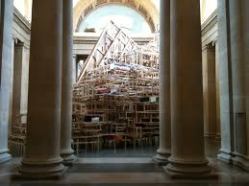

Buren does have interesting things to say about the homogeneity of the way in which artworks are currently shown – “according to the prevailing taste of a particular time.” But, according to his strictures, how then are we to recognise the different qualities of an artwork and does it matter how they are shown? This brings me to the works of artist Doris Salcedo. She often produces works for specific locations. For example, her collection of chairs is an entirely-site specific piece, located in the space between two buildings where an office had previously stood. This piece could not be made in a studio and could not be transported to a gallery after it was shown. What is more, the piece no longer exists, except as a photograph – a secondary image – a chimera of the original and not the original. It is therefore, not prey to the hostile gallery environment. Rather, it is miraculously free.

Doris Salcedo Chairs

Buren finally nails his colours to the mast when he talks about the sense of reality and truth that works seen in the studio have. I have problems with notions of truth in a work, as do many other commentators. As Foucault wrote in the History of Sexuality, that by some process of confessional, the individual (or work), can offer up something true as opposed to something false.

Raymond Williams makes an interesting point about where art is made and displayed and the status conferred upon it. He argues that status is based on whether or not it is actually seen by anyone. In a comment on ancient cave paintings he says: “they, (cave paintings), are now generally seen as art, indeed in many examples as mayor art. Yet, they are commonly sited in dark and inaccessible places…” Raymond Williams The works of Art Themselves, ‘Identifications’ Cullture, Fontana Press, London 1981 p119. Williams argues that we would not deny these works the status of major art works if they had been seen only by the person who made them, until of course we had, perchance, come across them. This raises questions about the studio verses gallery, shall we say the display conundrum. If a work is not seen, even outside of its place of manufacture, would we not want to recognise it as art at some later date? Indeed, Buren sidesteps answering the question about whether something is an artwork at its time of making or something else.

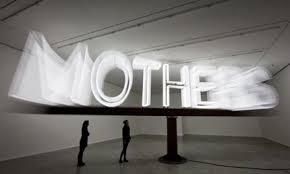

The case for installation art, throws Buren’s argument further into relief. Installation works are often site-specific and frequently made/assembled/created where they are to be shown. Indeed, Mike Nelson has, as Claire Bishop says, “neither a studio, nor collectors. His work is about its engagement with a specific site”. It has, she argues, “a critical stance towards both museum institutions and the commercialisation of ‘experience’ in general”. (Page 44 Claire Bishop, Installation Art).

Mike Nelson Quiver of Arrows

In fact, Nelson’s approach to his art is to create scenarios that are scripted in advance. He uses, according to Bishop, a complicated web of references to film, literature, history and current affairs. The work then typifies a practice that is outside the studio gallery environment by its very nature. Salcedo’s work makes the same point, only more forcefully. Mieke Bal argues that Salcedo’s work, like her 2004 installation work Neither, “needs to be built in the specific space where it is subsequently shown, (it is) no longer sculpture because it is immovable. This point again makes an interesting dialogue with Buren’s point about moveable art. Bal also makes the point about the permanence of the Salcedo piece: “Once it is there, it is not possible to move it around to see if another arrangement would work better”. It is a unique moment caught where it is and remains there unless of course it is removed after a time and then maybe little or no trace remains. Bal argues that the 2007 piece Shibboleth ‘brings the artist’s relationship with space full circle’. The work had to be filled in after the shows end. The entire work all but disappeared under concrete. But as any visitor to the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern will testify if they look down, the work is not entirely lost. “Concrete always keeps a trace of what lies beneath. It loses relief but keeps colour, or rather discolouration. We can see colour as the remnant of life, persevering against all odds”. Bal 2012

Further to this, is the question of whether a readymade is an artwork according to Buren’s definition? After all, these are not made in an artist’s studio but are offered up by the artist for display. What then of the readymade transported to the studio and left there? And what of Performance Art? It is, neither made in a studio, and may never be experienced in an art gallery either.

Finally, there is an implied discussion in Buren’s piece about what is art. But this is a subject for another occasion. I have attempted here to discuss the gallery/studio vector through looking at the essay by Daniel Buren. His piece raises some interesting areas for consideration, but is undermined by a number of factors, not least of which is his lack of consideration of installation art and of performance art, which is the elephant in the room as far as his argument goes. And it is maybe, that he was taking a swipe at the growth of performance art of the 1960s (Fluxus group etc). He doesn’t mention it by name but then things are notable by their absence, about what is not said as much as what is, as Freud and others would no doubt testify.