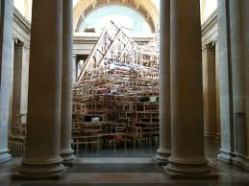

This is Barlow’s largest piece of work to date and dwarfs the Duveen Galleries at London’s Tate Britain. As a huge fan of her work and contribution to contemporary British Art, I was full of expectation.

It’s a magnificent piece, there is no denying, stretching almost as far as the eye can see along the length of this central atrium within the gallery. That is if one could see the whole sculpture as a complete whole. But, you cannot do this as its many elements obscure a total view of the whole. Instead, the viewer is forced to negotiate around the work, weaving a path, where one large object obscures your path and your ability to see.

Dock contains all of the Barlow elements, lots of wood, lots of packaging material (black bags, parcel tape, string, rope) and reused material – at least, it appears to be reused, but given that this is her biggest work, its hard to see where all the material comes from, so I am assuming that much is new but made to look reused. This leads one to consider how much the recycling of materials from one work to another is part of her USP, or whether it is just a practicality based on the contingency of cost and the type of materials and aesthetic she embraces. I am not sure I really have the answer to that one here. So let’s assume that some of the wood bearing the traces of dripped paint is reused from earlier pieces (if it isn’t, it manages to effect that conceit very convincingly). Then this work begins to gel as part of the Barlow canon.

But I am not convinced that upsizing her work has lead to the masterpiece I was expecting. Yes it’s a brave work and yes Tate’s director, Penelope Curtis has to be applauded for commissioning this work, but it’s not a fully resolved piece in a number of respects. The high structures, which resemble Russian wood scaffolding (at least Soviet era Scaffolding, I’ve not seen the post era stuff) give the elevation that Barlow has successfully utilised in the past, I’m thinking of the work in the downstairs lobby of her recent Hauser & Wirth Piccadilly show. What’s missing in the Tate piece is something of the vulnerability of that work, the precariousness of the elevated objects on flimsy stems. At the Tate the structures are rigid and box like and feel stable, even if some elements over hang them.

So what’s missing from this piece is some of the vulnerability of her earlier works and also some of the colour and curiosity too. Elements look derivative like the large tube structure and the high platforms have echoes of Tracey Emin’s raised seaside chalet or big dipper in structure and material but lack the interest Emin’s does and the vulnerability she engenders. Also, the desire to see above our head height which Emin’s work provokes. This is lacking in Barlow’s work at Tate and was so masterfully there at Hauser & Wirth where you could see up close from the upstairs balcony what you could only glimpse and imagine from below. Now I do chide myself for not looking at Tate Britain from the member’s lounge or its environs on the upper floor to see whether there were any elevated views of Barlow’s Dock, and it is possible there are.

The Barlow Dock, has echoes of the riverside activity of times past on the adjacent Thames, but it seems like a flimsy hook to base the work and is also not necessary to anchor the piece. It does not add to the work and it quite possibly detracts by over determining responses to the piece, stripping it of enigma and encouraging viewers to read things into elements that might not be helpful. There was one element that I think really didn’t work and that was the collapsed piece that looked too self-conscious. We are all well acquainted now with the language of sculptural pieces that have constructed and deconstructed echoes side by side. It’s no longer necessary and looks jokey in a more visually enlightened age. We need to develop a new vocabulary, that language has been thoroughly explored and feels dated.

There is much to admire and I will certainly visit again, but I think this large commission has been an important learning curve for Barlow as it should be for all artists who are encouraged or are contemplating up-scaling their work. Sometimes it does not come off. We need to treat the urge to up size with extreme caution. It might be that Barlow’s work does not suit the grand gesture like this and is better small. And on that note lets hear it for the smaller artwork, sometimes less is more and we shouldn’t feel embarrassed or uncomfortable with that.