“For my part, I think we need more emotion, not less. But I think, too, that we need to educate people in how to feel. Emotionalism is not the same as emotion. We cannot cut out emotion – in the economy of the human body, it is the limbic, not the neural, highway that takes precedence.” Jeanette Winterson, (2009).

Winterson writes of the importance of emotion, yet within contemporary fine art, emotion is something of a dirty word. There are several questions I want to address in my research. The first is whether there can be a place in contemporary fine, and my practice in particular, for emotion. The second is what role emotion and memory, especially the memory of traumatic events, play within my work. There is a further question related to the second one, which I can only explore by experimenting with my artwork, and that is whether it is possible to represent traumatic events without bestowing on them a mimetic aesthetic as Theodor Adorno cautioned. (Adorno, 1965, 125-7).

Gregory Hayman, 2013, Darkness Covers All still

My method of working involves a deep immersion and contemplation of ideas, objects and materials. My work Darkness Covers All resulted from such an inquiry. Or witness my recent interest in the film The Hours, an homage to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. I’ve watched the movie many times, replaying sequences. I have read both books and listened to the soundtrack a hundred times. I have watched the DVD’s special features, read reviews and critiques of the film and books. This may result in an artwork but understanding my interest is no clearer; I therefore need a conceptual or theoretical underpinning for my inquiry.

Part one

In the first part of this report I look at some of the approaches to research and fine art practice. Gillian Rose (2007), discusses a range of methodologies for analysing artworks, images and visual material including; composition interpretation; content analysis; semiology; psychoanalysis; discourse analysis (including text, intertextuality, context, institutions and ways of seeing) audience studies; and anthropological approaches. I found her survey a useful overview, and want to focus on discourse analysis, psychoanalysis and content analysis.

Rose sums up the usefulness of discourse analysis thus: “(it) can be used to explore how images construct specific views in a social world, in which physiology is viewed as the topic of research, and the discourse analyst is interested in how images construct accounts of the social world. This type of discourse analysis pays careful attention to an image itself (as well as other sorts of evidence). (Rose, 2007, 146)

Rose also argues that discourse analysis addresses questions of power and knowledge, which of its very nature, pays careful attention to images and social production and effect. She cites Phillips and Hardy (2002) who claim that discourse analytic methods are inherently reflexive. Putting an opposing view, Rose cites Michel Foucault, who in his introduction to The Archaeology of Knowledge derided autobiographical reflexology: “do not ask me who I am and do not ask me to remain the same: leave it to our bureaucrats and police to see that our papers are in order” (Foucault 1972). So, whilst I find the possibility of reflexivity useful in addressing at least part of the questions I have posed, I am aware that there are shortcomings if I follow Foucault’s logic. Should I then turn to psychoanalysis for answers?

Kristeva looks at the psychoanalytic interest in the search for the ‘lost object’ or thing. She describes the mechanisms for dealing with mourning and this seems to echo the processes of memory that underpin elements of my practice: ‘art seems to point to a few devices that bypass complacency and, without simply turning mourning into mania, secure for the artist .. a sublimatory hold over the lost Thing’. (Kristeva, 1993: 203) However, even Freud had difficulty in understanding mourning describing it as a ‘great riddle’. For the purposes of my practice, (but not in this discussion), I need to devote more research to the psychoanalytic elements in the link between emotion and an artwork, both in its production and reception.

I turn now to the potential of content analysis. Using this methodology, it emerged that there are a range of devices used to manipulate an audience to promote an effect. Most emotionally charged art forms seem to have a combination of denial and sacrifice, some even have the death of one or more of the protagonists with which the viewer is made to feel sympathy or identify. With music, it seemed to be the use of minor keys and the combination of solo string instruments and the build towards a climax. I have looked at a wide range of material: from films like The Hours; A Brief Encounter; Casablanca; and The Third Man, and art films like Brontosaurus, and Viola’s films. I have also listened to operas like La Traviata and Aida; film scores; and read a large number of novels over the past months. The purpose was to try and identify whether there were any common ingredients, mechanisms or ways of positioning emotion or contributing to the production of an emotional response.

Still from Shed film Gregory Hayman 2014 after sequence from The Third Man

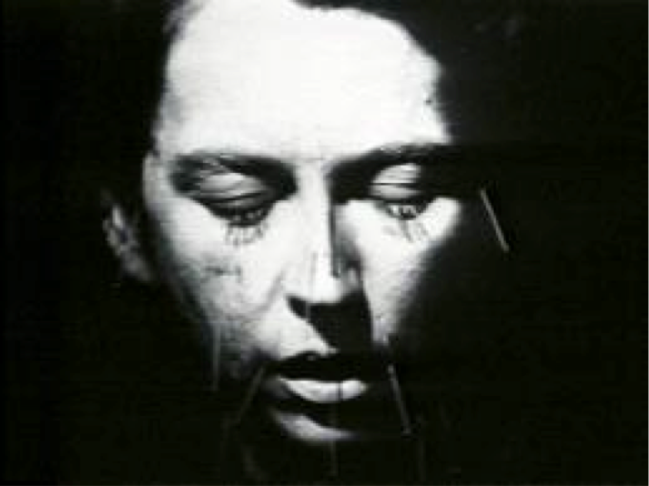

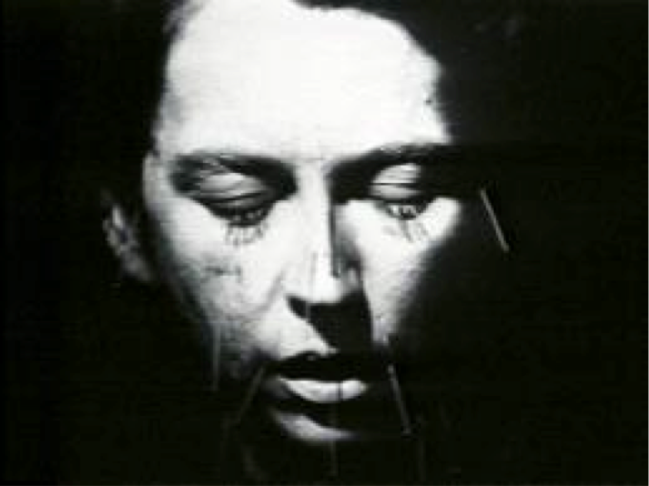

With all approaches to my enquiry I have engaged with a wide range of critical writing. Jennifer Doyle’s: Hold it Against Me – difficulty and emotion in contemporary art, attempts to explore some of the terrain for difficulty and emotion in performance art, painting and photography. Doyle singles out the film by Linda Montano entitled Mitchell’s Death (1978), which deals with intense grief where the subject appears to be literally and metaphorically numb to it: “Mitchells Death emerges as a black hole, an absence that organizes the space around it. When Montano’s voice and image fade, they seem to recede into the void.” (Doyle 2013, xi) To be sure, Doyle sets herself an ambitious project: ‘to dismantle the mechanisms through which emotion is produced and consumed.” (Doyle 2013, xi)

Linda Montano, still from Mitchell’s Death (1978)

However, there is a problem with Doyle’s methodology in that she collapses the terms ‘emotion’, ‘feeling’, and ‘affect’ whilst admitting, that she uses all three rather loosely: “I resist the identification of categorical differences between these terms. In my view, such efforts belie the complexity of the experiences I am describing – or, at least, a typography clearly delineating one from the other would not forward the kind of conversation I am staging… ” (Doyle, 2013, 146). This failure to try and distinguish between the three terms is emblematic of the reluctance by critical thinkers to address emotion in the arts. To be fair, Doyle struggles with her own response to some other work she discusses. She begins by looking at ‘difficulty’ and this skews and defines her developing thinking on the subject. It is quite easy to find works that are difficult or that deal with difficult subjects, but it’s not the same as looking at works that deal with emotion or provoke an emotional response. Clearly, sometimes they overlap but they are quite different. Equally, it is possible to argue that both are historically and culturally specific in as much as say abortion can be. On the other hand, grief and loss are universal, whether individuals and societies choose to ritualize their responses to them differently. In other words, they may be historically and culturally specific, but they nonetheless try to organize and give voice to a similar emotional response.

I do not want to deal with difficult subjects specifically in my artwork or my research, although sometimes I may touch upon them. I am more interested in trying to unravel whether emotions can be rendered possible in contemporary fine art. What Doyle correctly identifies is a type of artwork that turns the viewer into a witness or even a participant. This interpolation of an audience makes people feel uncomfortable and provokes a response that Doyle says can be distinctly personal. (Doyle 2013 xvii). Doyle’s thinking about emotion and art centres on the nature of expression that she says is inextricably linked to questions of identity, which she says, actually “dissolve in emotion”. She continues: “emotion can make our experience of art harder, but it also makes its experience more interesting. It may make things harder because the work provokes unpleasant or painful feelings. It may also make things more complicated; and artwork might provoke contradictory feelings, and it may provoke in the viewer feelings that are at odds with the effective culture of its context. Emotions themselves are very complicated. They can be impossible to stabilize. For example, none of the following questions is easy to answer: does a feeling come from inside the spectator or from the artwork? Does an artwork represent feeling? Whose: the artist’s or the viewer’s? Does a work make feelings? How?” (Doyle, 2013, 4).

Part two

“I can only note that the past is beautiful because one never realizes an emotion at the time. It expands later, and thus we don’t have complete emotions about the present, only about the past.” Virginia Woolf, 1939.

Woolf suggests that emotion only reveals itself with time. My art practice is concerned with memory and how artist’s attempt to memorialize traumatic events. My undergraduate dissertation looked at how artistic responses to traumatic events, like the Holocaust and 911, change over time. I used the Five Stages of Grief model to account for how artistic responses are linked to time and Woolf suggests that consideration of time is paramount, as the grief model indicates.

This raises the question of why some elements of an artwork or some artworks appear meaningful and others not? Is this where a consideration of time kicks in, or where time intersects with the part memory plays? It could just be that the things that appear significant are the things that are memorable and that they are memorable because they are what we choose to remember or it could be because they touch some other internal subjective chord which develops over time.On the other hand, memory could be constructed and so too could our emotional response. Patrick Fuery argues that meaning in film is based on a kind of madness or delusion: “madness operates as the otherness to meaning, interpretation, knowledge, and so on.” (Fuery, 2004, 154). But Fuery also believes that this part of the meaning structure actually derives from the cinematic apparatus. According to him, everything from cuts, sounds, camera angles, lighting are all meaning producing systems because they have meaning beyond the film (Fuery, 2004, 157). This does not quite answer the time based elements, but might answer the nostalgic pleasure derived from repeat viewings.

Conclusions

“The fact of the matter is that, since we are determined always to keep our feelings to ourselves, we have never given any thought to the manner in which we should express them.” Marcel Proust, (1913, 231)

I have tried to analyse some of the methodologies for researching visual materials like compositional interpretation; content analysis–counting what you think you can see; semiology; psychoanalysis; discourse analysis–intertextuality and, text; and audience studies. A problem I became aware of was that by listing these methodologies, a process of ranking them began to emerge. I am not clear whether I want to rank them, or whether I am implicitly ranking them and if so, what significance one methodology has over another. It is possible that they might be interacting or are co-dependent.

I am aware that the question about emotion I set myself was slightly bloody-minded in that I like to tilt at orthodoxies and don’t like subjects that are out of bounds. My approach to questions and research underpinning my practice might actually be unconventional in this respect. Smith and Dean locate the problem of conventional definitions of research: “at the basis of the relationship between creative practice and research is the problematic nature of conventional definitions of ‘research’… That research is a process which generates knowledge, but takes knowledge as being an understood given.” (Smith and Dean 2010, 2-3). They point to the notion that knowledge is often regarded as both transferable and general and also presuppose the works can embody knowledge with these attributes. I tend to agree with them that research is not monolithic but as an activity “which can appear in a variety of guises across the spectrum of practice.” And the same must apply to orthodoxies.

Smith and Dean also talk about practice-led research and research-led practice, which sums up the iterative and circular nature of research and practice – how one feeds the other, I do feel that sometimes I am caught on a hamster wheel and that might not be such a bad thing. It might even be inevitable.

In summary, I have attempted to scrutinize my practice by posing questions concerning emotion and memory and to give thought, as Proust suggests, to the way in which emotion might be expressed. What I have found is I may have to unravel emotion from notions of knowledge and meaning. Furthermore, I may need to research how viewers respond to technical forms of artistic language. Above all, I am now committed to an on-going enquiry involving research and practice.

Bibliography

Adorno, T. (1965) Engagement. In Noten Zur Literatur, vol. 3. Frankfurt. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Bennett, J (2005) Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford. Stanford University Press

Blatter J and Milton S (1981) Art of the Holocaust. The Rutledge Press.

Cassiman, B. (1993) The Sublime Void. On the Memory of the Imagination. Antwerp. Ludion.

Collins H (2010) Creative Research. The theory and practice of research for the creative industries. Ava Switzerland.

Doyle J. (2013) Hold It Against Me–difficulty and emotion in contemporary art, Duke University Press, Durham and London,.

Gray C and Malins J (2004) Visualising Research: A guide to the research process in art and design. Ashgate, London 2004.

Ksisteva, J. (1993) in The Sublime Void. On the Memory of the Imagination. Antwerp. Ludion.

Proust M (1913) The Guermantes Way Vol. 3 of Remembrance of Things Past Translated from the French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, Adelaide Books, Adelaide.

Rose G. (2007) Visual Methodologies: an introduction to the interpretation of visual materials (2nd edition) Sage Publications, Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore.

Saltzman, L (2006) Making Memory Matter – Strategies of Remembrance in Contemporary Art. Chicago & London. University of Chicago Press.

Smith H. and Dean R. T. (editors) (2010) Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh University Press Edinburgh (reprint).

Sontag, S. (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others. New York. Pearson.

Sullivan G. (2005) Art Practice as Research: Inquiry in the Visual Arts. Sage, Thousand Oaks, London, Delhi.

Winterson J. (2009) The Stone Gods, Mariner Books, London.

Woolf, (1939) A Sketch of the Past, from Moments of Being, published posthumously.